|

| The Phoenix Police Headquarters

at Washington and 7th Avenues. 8-01 |

For better than 40 years police have

been reading suspects their rights because of a landmark 1966 United

States Supreme Court case, Miranda v. ArizonaM1

That case had its origins in an interrogation room of the Phoenix

Police Department.

Ernesto Miranda was an eighth grade drop out with a criminal

record and pronounced sexual fantasies. On March 13, 1963,

Phoenix police went to his home and arrested him for the kidnap and

rape of a mildly retarded 18-year-old woman. He was taken to a

police station where a witness identified him. Two officers

questioned him in "Interrogation Room No. 2" of the

detective bureau. Two hours later, the officers emerged from the

interrogation room with a written confession signed by Miranda.

The confession had a paragraph typed at the top which stated the

confession was made "with full knowledge of my legal rights,

understanding any statement I make may be used against me."

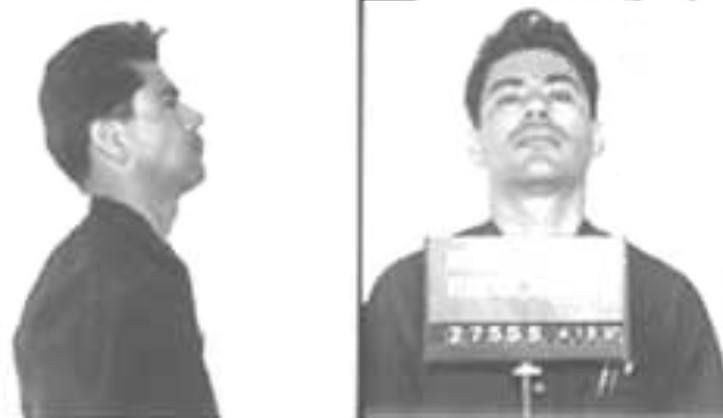

|

| Ernesto Miranda, 1963.

Public domain. |

At trial, no evidence was presented that Miranda had ever been

told that he did not have to talk to police or that he had the right

to a lawyer. The defense objected to letting the jury see the

confession, but the judge overruled the objection. He allowed

the jury to consider the written confession as well as officers

testimony about an oral confession made during the interrogation.

The jury found Miranda found guilty of kidnapping and rape.

He was sentenced to 20 to 30 years on each of the two counts, to be

served concurrently.

|

| The "old" Maricopa

County Superior Court Building at Washington and Central

Avenues, erected in 1928. 8-01 |

The Supreme Court of the United States reviewed the case and

found that Miranda's Fifth AmendmentM2

right against self incrimination had been violated. Chief Justice

Earl Warren wrote the majority opinion of the Supreme Court which

stated that in order to combat the "inherently compelling

pressures which work to undermine the individual's will to

resist" during in-custody interrogation, "to permit a full

opportunity to exercise the privilege against self-incrimination,

the accused must be adequately and effectively apprised of his

rights and the exercise of those rights must be fully honored."

The court's opinion went on to state the now familiar statement

beginning with "You have the right to remain silent."

The result of the failure to give the Miranda warning does not

automatically result in the defendant going free. It only

means that the confession cannot be used against the defendant.

Ernesto Miranda was tried again without the confession. He was

convicted and served 11 years before he was paroled in 1972.

After several other returns to prison on other charges, he was

stabbed to death during an argument in a bar in 1976. He was

34. A suspect was arrested, but he chose to exercise his right

to remain silent after being read his Miranda rights. The

suspect was released, and no one was ever charged with the murder.

|

| Grave of Ernesto Miranda at the

Mesa City Cemetery. The inscription in the blue border

at the top reads, "Beloved brother and friend."

3-02 |

The Miranda decision was seriously challenged when Congress

enacted 18 U. S. C. �3501. That statute allows a confession

to be admitted into evidence if it is found to be voluntary, even if

the defendant was not given the Miranda warning. The Supreme

Court reviewed this statute in Dickerson v. U.S., No. 99-5525 (June

26, 2000), and found that it was an invalid attempt to change the

result of the Miranda case. In a 7-2 vote, it held that the

Miranda warning requirement was based on the constitution, and that

Congress could not change it by legislation. As a result, the

requirement that the Miranda warnings be given in order for a

statement of the defendant to be admitted into evidence continues to

be the law, and has an ever greater majority on the Supreme Court

than the original holding. |

|

Footnotes and Sources for Mirandizing the Nation:

M1. Miranda

v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966). The Miranda case from

which the rule takes its name was one of 4 cases combined for review

by the Supreme court where a confession taken without the defendant

being advised of his rights was admitted at trial. The other

cases were: Vignera v. New York [Michael Vignera was

convicted of the robbery of a Brooklyn dress shop. He was

subsequently adjudged a third-felony offender and sentenced to 30 to

60 years' imprisonment. Lower court conviction reversed.]; Westover

v. United States [Carl Calvin Westover was convicted of

robberies of a savings & loan and a bank in California. He

received two consecutive 15 year sentences. Lower courts conviction

reversed.]; California v. Stewart [Roy Allen Stewart

was convicted and sentenced to death for robbery and murder arising

out of a purse-snatch robbery in which the victim had died.

Appellate court's reversal affirmed.] John J. Flynn argued the

case for Miranda, and Gary K. Nelson, Assistant Attorney General of

Arizona argued the case for the State of Arizona.

M2. "No person

shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime,

unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in

cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when

in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any

person be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy

of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to

be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty,

or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property

be taken for public use, without just compensation."

"Bill of Rights," Constitution of the United States,

Amendment V. [Emphasis added.]

________, "Miranda

v. Arizona," britanica.com,

accessed 7-28-01.

________, Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966).

Full text may be accessed at "MIRANDA

v. ARIZONA," Touro

College Law Center, accessed 7-28-01, and "MIRANDA

v. ARIZONA," FindLaw

for Legal Professionals, accessed 7-28-01.

________, "Supreme

Court reaffirms that police must read Miranda rights to criminal

suspects," CNN.com,

accessed 7-28-01.

________, "What

is the Miranda Warning?", CourtTV

Criminal Law, American Lawyer Media, L.P. and Little, Brown and

Company, Inc., accessed 7-28-01.

Gold, Susan Dudley, Miranda v. Arizona (1966),

Twenty-First Century Books, New York, 1995.

Riley, Gail Blasser, Miranda v. Arizona, Rights of

the Accused, Enslow Publishers, Hillside, New Jersey, 1994.

Warren, Earl, Warren's

handwritten notes concerning the Miranda decision, American

Treasures of the Library of Congress, The

Library of Congress, accessed 7-28-01.

Wice, Paul B., Miranda v. Arizona "You have

the right to remain silent...", Franklin Watts, Danbury,

Connecticut, 1996. |